|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

October Fly-Bys

|

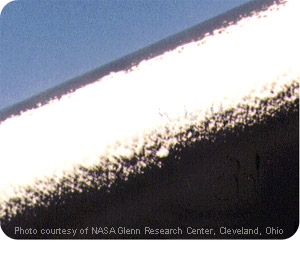

| Rime Ice Rime icing is brittle, opaque and milky colored. It’s formed when water droplets rapidly freeze on the aircraft structure. |

|

|

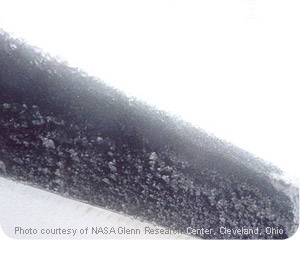

Clear Ice In contrast, clear, or glaze, icing is dense. It is less opaque, forms a thin, smooth surface and tiny rivulets, and appears streaked or with bumps. Clear ice is occurs when water droplets slowly freeze. |

| Mixed Ice Mixed icing combines the characteristics of both rime and clear ice. It is denser than rime and harder to remove. Mixed ice will form in non-uniform clouds at temperatures that permit a “moderate” freezing rate. |

|

When and where the risk of icing is greatest

Five locations lend themselves to the greatest potential for icing. These are cumulus clouds, mountainous regions, the downwind sides of large lakes, in supercooled fog, and within weather fronts.

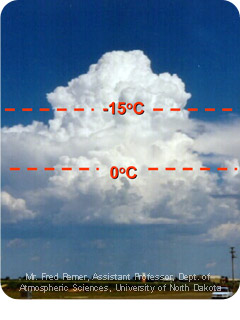

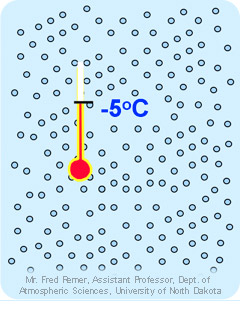

| Worst Icing Conditions Strong updrafts, high liquid water content and large drops characterize cumulus clouds. In cumulus clouds, the worst icing will occur at altitudes where the temperature ranges from 0 to –15º Celsius, and is possible in any season. Clear ice is common in cumulus clouds, and it can be severe. |

|

|

Mountains provide a constant source of atmospheric lift and cloud formation. Costal ranges, with their proximity to massive sources of moisture, are particularly fertile locations for icing to occur. Mountain clouds tend to be young clouds containing a high liquid water content. Accelerated lift in mountain regions plus the greater likelihood for icing can quickly marginalize aircraft performance. |

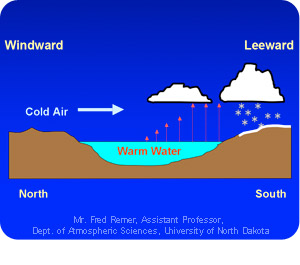

| Lake effects also involve atmospheric conditions that provide moisture and unstable air. Clouds pick up moisture while moving over lakes, such as the Great Lakes, and carry it ashore downwind. Lake effect clouds generally are low, reaching from the surface to about 8,000 feet, and are most common in the fall and spring. Lake effect icing can be moderate to severe, and involve rime, clear or mixed ice. |  |

|

Supercooled Fog involves suspended liquid water droplets occurring in temperatures colder than 0º Celsius. Such icing is common in winter, often occurs while taxing, and involves rime ice. |

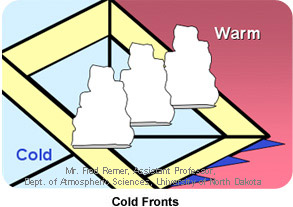

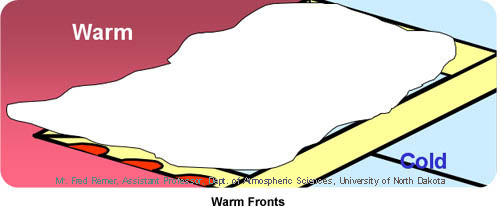

Warm and cold fronts spawn

icing condition throughout the year. Warm fronts

have a broad area of icing

across a wide

cloud

band. In contrast, cold fronts involve narrow

bands of icing and a

narrow cloud band. Pay special attention to

flight planning in these regions

to avoid icing conditions.

Five good URLs you should know about and use to help avoid icing

are:

- Forecasting Aviation Icing: Icing Type and Severity

- Aviation Digital Data Service (ADDS) Icing Page at the Aviation Weather Center

- Icing Branch at NASA Glenn Research Center

- More Icing information from AOPA

- To take a NASA Course on Icing, follow this link by going to weather, then icing